Governments that aspire to improve the performance of public commercial assets, owned by entities such as companies, financial institutions, and utilities, instinctively appreciate the need to demonstrate that the business is not encumbered by any policy agenda or unfair advantage which could risk crowding out private sector competitors and distort the market.

The task at hand is to compensate for the previous and often inherent weak governance practices arising from conflicting objectives, poor incentive structures, political interference, and the lack of public scrutiny. This remains a constant struggle as long as there is a government ownership involvement in the asset.

Introducing professional governance of government owned assets requires politically difficult choices for governments in both developed and developing countries. The technical issues are rather simple and managed every day in the private sector. The challenge depends entirely upon the will of the political leadership. But the evidence is clear: commercial governance of assets generates material gains for society as a whole.

This was clearly demonstrated when Sweden restructured its portfolio of some 60 public commercial assets on the back of the financial crisis in the 1990's, where deregulation and an increasing globalization had exposed the flaws of state capitalism. The Swedish government portfolio had been a protected part of society managed by a small elite of people that had lost sight of a common purpose. The financial statements laid bare the fact that the model was in desperate need of radical change.

One of the tools used to transform the portfolio was recruiting relevant professionals able to execute the fundamental restructuring of each company. More than 85 per cent of the Non-Executive Board members and 75 per cent of the CEOs in the portfolio were replaced over a three-year period, in total several hundred people. The result was an overwhelming improvement in performance, with the portfolio outperforming the local stock market.

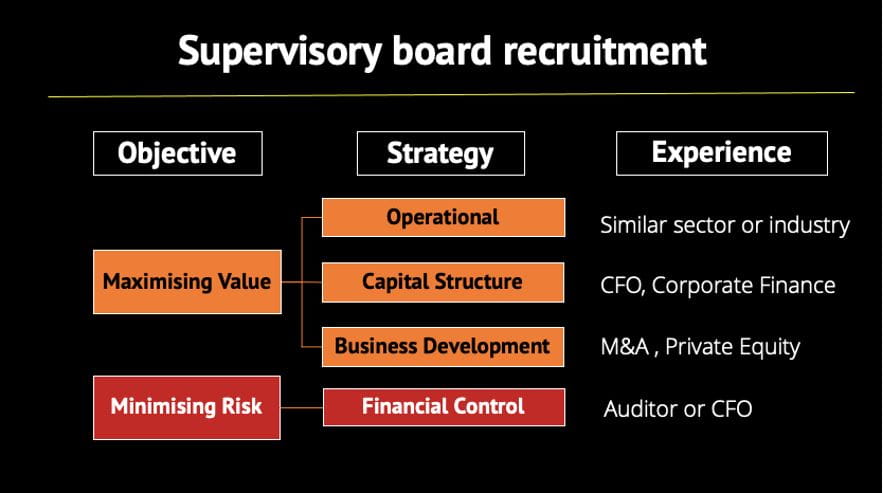

In the commercial world the aim is to create value, which is based on three fundamental strategies: operational, capital structure and business development. Ideally, each Non-Executive Director should have a background in at least one of these areas to be useful to the board, in addition to general senior corporate governance experience (see Chart below). Each should also have the capacity to share and debate issues from their wealth of knowledge and deep experience. These attributes are what will make the board a useful tool and give it a competitive advantage when developing the business. The complementary and equally important objective to maximising value is optimizing risk – which explains why financial control must always have a strong emphasis in the recruitment process.

Operational experience can be found in people having a relevant background and track record of improving the margins in similar businesses, combined with the general skills in overseeing a complex business. For example, the board of a financial entity might want to recruit bankers from a similar segment of the financial industry, with the associated specialized skills.

Optimising capital structure is a never-ending struggle for the best mix of financial instruments and maintaining balance between debt and equity in a constantly evolving financial market. Recruiting a Chief Financial Officer from a similar sized business, or a person with a strong background in corporate finance, can be very valuable.

The importance of business development varies depending on the industry, its stage of development, and the timing of the market cycle. Many entities managing government-owned assets have an innate tendency to become conglomerates. To achieve a more efficient use of capital they will therefore need to focus on their main business and divest of non-core assets. Likely candidates covering this strategy would have experience of managing a similar size and complexity of transactions resulting from mergers and acquisitions at an international bank or industrial company.

Minimising financial risk, however, must never be underestimated. Robust financial control requires the best possible expertise available at all times, regardless of the development phase and market situation. Financial control can never be achieved with hindsight. Like personal health, the groundwork is made years in advance. The experience required for this potential non-executive director is often found in senior people in international auditing firms or with the CFO of a business of similar size and complexity.

Boards tasked with managing a commercial business are not democratic institutions that require equal representation of the population. They deliver good outcomes only if they are staffed by individuals who know how a commercial business works. Persons with a background such as politics or academia and without the relevant commercial experience in maximising value or minimising risk would often find it difficult to contribute. It is rather like a football team or a symphony orchestra. Every Non-Executive Director must not only be able to add value to the enterprise, but also enhance the dynamics of the board as a team.

The role of the chair, as captain of the team, requires an ability to inspire a concerted effort to achieve the best possible commercial results. In addition, the chair should be able to communicate with both commercial and public stakeholders. This would not require a political background, merely skills as an entrepreneurial networker and communicator.

As governments face unprecedented financial challenges, from recent global economic shocks and the consequences of climate and demographic change, the need to mobilise all available resources is urgent. Recruiting professionals as Non-Executive Directors to manage the portfolio of public commercial assets will help increase fiscal space and reduce fiscal risk.

This process would benefit from being run in parallel with an effort to strengthen countries’ general corporate governance framework. The two efforts would reinforce each other and promote a better investment climate not only for the individual assets, but for the country as a whole.